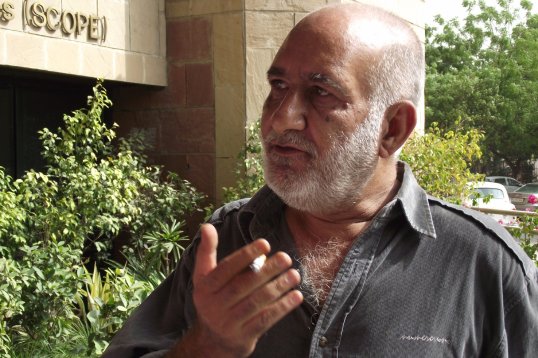

Cultural Class Always Looks for the Fantasies of Sacrifice, Failure and Suffering- Kamal Swaroop

By Kamal Swaroop

( A Genius film director and scholar )An Interview

Why has Kamal Swaroop become the symbol of mistaken genius; a case study in an artist’s tragedy?

If I was competitive and rich I would not have been framed as a genius: rest, cultural class always looks for the fantasies of sacrifice and failure and suffering. Maybe I was available as a subject of their anthropological imagery. Even when I was in FTII, every one called me genius without a solid reason to back that claim up. I never wanted to make a film, but I would talk a lot and reject most films. People challenged me, thus, to make a film myself. Om Dar B Dar was my response.

What do you identify yourself as? An example to avoid, an obsessive compulsive auteur who held dear his personal vision the most and paid the price for it, or just another film lover?

One of the ex students from the FTII direction course. I can only do what I can do. In art you can’t adopt some one else’s example, you can only represent where you come from. Om dar b Dar is Ajmer. As for being an example to avoid, I would just say – each for himself and cinema against all. I have had a terribly joyous and unframed life.

Is the oblivion a self-imposed exile or are you a victim of circumstances – of being cursed with the gift of being way ahead of your time?

(The irony is) I never fancied myself as a film maker. And feel very happy with the small work I do on mini dv or a multimedia project on Phalke. I also work on other people’s projects. Yes, I accept that I was good in whatever I did. If I was young in today’s time I would have been counted amongst the nerds.

What, according to you, is cinema? What does it constitute in its most original conception?

Resurrection: Individual as in Christ, mass as in the story of Bhagirathy, mass resurrection of children of King Sagar.

Most of the modern-day imagery, such as the one that features in advertisements or even in Bollywood films, basically attempts to and successfully does bypass the logical faculty of the viewers who watch them – addressing, instead, only the most primal, basal and fundamental of the human psyche. Why do you think images around us are getting increasingly redundant?

Most of the best brains from arts and craft are involved in the business of advertising and entertainment industry using the best available technology. They work according to the marketing briefs, i.e each spiritual problem has a material solution. We cannot really expect a philosophical rendering of a subject from them.

Why, looking at the examples of someone like you, or Kumar Shahani, should a new-young filmmaker in this nation pick up his camera and believe that he can actually make it his pen and each film a personal diary entry? What should motivate him towards the attainment of such a personal goal?

Recording and documenting is an important function of cinema, or say storing, like they say stories as means of storing a mass of information. Or say iconography, a constructed representation of vast memory and events. Otherwise it is impossible to store this chaos as it is because of a lack of space. I would not compare camera with pen and paper simile since language has its own reality. But I do agree that there are many young people from NID or Srishti, going back to their home towns and making wonderful things. A decentralization of production is necessary. Otherwise Bombay Bandra home videos are being touted as pan Indian reality.

But again, pen and paper thing applies only to digital video, it would not apply to films that are industrially produced: That film is a result of coming together of many evolved skills and imagination and pushing the technology to its limit. We also have to consider the changing nature of exhibition and distribution, with coming up of smaller states, there is going to be a great need of film makers to represent and to fulfil the artistic needs of that time and space.

There are many young film makers coming out of NID, some from FTII who are returning to their roots and their cities, who do not feel the need to keep imaging Bombay. Like Akash Gaur’s Itni Door Bhagaya, Bela Negi’s Daayen ya Baayen or Ram’s Putaani Party. But to be like a chronicler of a place like the novelist in the older times, it would need a deeper commitment and the local development of the infrastructure. Like in the early 20th Century, the writers had the whole press and distribution system. But at the same time, the demand from the author is not an exclusive subjectivity but a responsibility towards a certain objectiveness towards the people and their history.

Why do you think Parallel Cinema ended of all a sudden, much like Arthur C.Clarke’s Rama? Did it achieve the aims it set out to accomplish? Was it effective, or did it run, as is suggested, only ‘parallel’ to the mainstream, thus never attempting to influence the mainstream aesthetic in any manner? Did it exhaust its own possibilities? How important do you think was NFDC’s role in it?

Parallel cinema was an extension of the literary movement that took place during the 60’s and these writers also dreamt of a certain kind of a cinema and they facilitated the new film makers of that time. At the same time, the Times of India and also other, vernacular literary magazines were in full support of this new happening where the film maker was not just a merchant of entertainment but could be bracketed amongst the artists, ie writers, painters, sculptors. There was already a space for an author like this, in cinema. Realising available space like this, some of the FTII and other people with the unexpected arrival of FFC funding, jumped in. Among these authors, different positions were taken. We didn’t only have Mani Kaul or Kumar Shahani who saw their role and position amongst the international authors, we had people like Basu Chatterjee also who took the middle path and took it also as a business activity. He inspired so many film makers from the industry that he was easily taken in the mainstream. When the industry people realized that a person like KK Mahajan or AK Bir could take 75 shots in a day, the functioning of the industry changed overnight. Even the BR Chopras were inviting Basu Chatterjee to take over. So it is true that the parallel film people influenced the mainstream in a way. Then came the closing down of the TOI publications, like Saarika, Madhuri, Dharamyug, and a lot of other vernacular magazines, who were the mouthpiece of this parallel movement. Earlier these magazines were inspiring the imaginations of the readers and inspiring them to become film makers.

There was a production of these films upto a time, but there were no distribution and exhibition developed parallel with the production activity. Most of the films functioned as a cultural commodity for exchange with the European countries. This cultural commodification started creating new limitations and parameters- formulas within these films. But surprisingly the new generation today keeps looking for NFDC films.

You were a FTII graduate. You resumed your studies as a post-graduate. While you assisted in Attenborough’s Gandhi, where do you think the seeds of your largely formalist approach towards cinema were sown? How important do you think was the role of your vast reading of Indian literature in it?

My thinking changed after watching My American Uncle by Resnais. I was always an anti illusionist and wanted to do something about imagination and education. Or fictionalize philosophical essays. In his this film and his later films, I found a way.

Reading literature, it did help. I connected with Manohar Shyam Joshi’s sense of humour.

What defines the term avant-garde for you? And if can consciously appreciate its connotation, was Om Dar Ba Dar a conscious attempt at that type(avant-garde) of a film?

Avante garde is a technical term applied to a different movement. In Om Dar b Dar, I was reacting to the parallel cinema of that time. For example, I won’t say there are characters. I will say the film itself is a character. I was more interested in disconnecting and making the film that would work like a head cleaner. We used to call it brooming and presumed the role of a scavenger. And constructed a film based on the rejected.

Is Om Dar Ba Dar an event that you look back at with pride? Or do you look at it as an opportunity lost? Do you ever think you could have made a debut feature that evoked more embracement than intimidation?

Yes, with full pride. And no, I don’t.

You worked with ISRO in helping them produce Science Educational Programmes in the mid 1970s. A lot of Om Dar Ba Dar deals with a person’s simultaneous fascination with science, for instance the moon landing; and bewilderment with it – Om in his science class as he dissects frogs. Is that incorporation autobiographical? How instrumental was your work on the science educational programmes in shaping you as a filmmaker?

During ISRO times, we used to make science programmes based on the Russian books where they used to explain scientific phenomenas through fairy tales and parables. These books used to be a mix and match of playfulness, imagination, and magic tricks. For example I did a programme called System and Interaction, which was a complex subject by itself, but by taking a story of Jack and the Beanstalk, it became very easy for a child of eight to understand. This was the time when we were hobnobbing with scientists, product designers, architects, graphic artists, anthropologists. I must have been around twenty two years old and it was great in my formative development.

It came in the wake of an era in Indian cinema where everything had fallen into the dark ages – the VCR had entered people’s homes, television was(and is still) becoming increasingly lucrative, and producers from the South had imported their inane ostentatious approach to Mumbai. Was, your film, at a level, aware of this era; or did you plan it as an entrance into another newer one?

I was aware of all the happenings and wanted to make my film as a force that would have to be reckoned with by the new order. My effort was appreciated even by the commercial industry, the Filmfare being the validation of that claim. With Om Dar Ba Dar, it seems you are consistently attempting a departure from the aesthetic of the parallel cinema, and also its thematic concerns. It is almost as if your film is an expose of the hypocrisy of the other films produced by NFDC.

You set your film in a small town, but instead of demystifying and simplifying the residents of that town, you deliberately choose to enhance their mystery and present them as entangled in far greater issues than mere sociological concerns. As such, your characters are first human and then trigger points for greater issues, a complete antithesis of the films of someone like Shyam Benegal?

Those days we used to call this middle wave cinema “Complaint Box”. What more can I say?

Do you think the narrative is a burden that cinema has fallen in eternal servitude to? Is it like lyrics are to music? Considering, also, that your film uses the narrative only as an excuse to traverse greater ideas – some of which are Om’s identity crisis, the hypocrisy called Indian culture, Gayatri’s sexual deprivation, curiosity related to adolescence, and the move from adolescence to adulthood? In that sense, your film is almost anti-narration.

Usually I start constructing a screenplay by dreaming of images and shuffling them in my mind. Then I note them down on paper. Since I am very weak in thinking in languages, I work in a way which in the end takes a story form as a way to keep these images together. But surprisingly, I never read what I write. The screenplay is basically for the production break down. I keep processing the images in my mind till the last moment and not relying on the fixed image on paper.

You’ve written that cinema was essentially conceptualized through the incorporation of the concept of a cyclic loop, but as the medium progressed, the events within a story were reduced to a linear progression, with one thing happening at a time, and more importantly never happening again. Was your film a return to the idea of the ‘loop’; the ‘ellipse’?

This kind of a conceptualization I only developed after I was working on the Phalke project. During Om, I was not aware of it. But in Om, the images keep repeating in different shapes. And adhering to a musical system of returning again and again. And arriving at a ‘sam’.

You also deliberately dissociate sound with related imagery at various points in the film; for instance when Om’s father is indicted for conning people through fraudulent astrology, and you shoot him from a roof into the crowd and a voiceover announces the court’s judgement – was it done to make the audience consistently aware of the element of sound that they had taken for granted?

Since I couldn’t illustrate all the information that I wanted to give to the audience, I was making the best use of the filmic time available.

Om Dar Ba Dar is a film that exists in the form of mythic folklore in the annals of Indian cinema history. Most film lovers know about it; but most haven’t watched it. You have written that it’s a Dadaist film. Which would mean that you were fighting against an established order to you’re your ‘chaos’. What was that ‘established order’ for you? Even then, demystify it for us.

It is a fictional film set in Ajmer.

That done, tell us about your involvement with Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro.

I was doing research on that project and used to go to Bombay Central, Grant Road, interviewing small gangsters operating in various byelanes, composing a prototype of Salim, the protagonist.

Ever since Om Dar Ba Dar, you’ve made documentaries in association with the PSBT. Why do you think the documentary form has assumed a didactic status in the realm of Indian cinema, and why is no longer an exploration; but a lesson? What do you think is the reason behind its waning popularity.

There is a mix of kinds of achievements and intention in documentary today, just as in earlier times, during the Film Division times. But once in a while, we find very well realized short films and documentaries within this funding system.

For the last 20 years, you have been working on a documentary project tentatively entitled The Life and Times of Dadasaheb Phalke. With a current film, Harishchandra Factory, winning critical accolades, where do you think your effort stands in terms of its relevance?

With the coming of Harishchandra Factory, people have taken a renewed interest in my project. Personally I really don’t know what kind of a form, in the end, my project is going to take and the number and the kind of off shoots.

Why the fascination with Dadasaheb Phalke? A fascination which stretches into your exhaustive reading on him, and accumulation of different resources of information on him? So much so that you’ve had to scrape through and seek artist funds to maintain a normal lifestyle.

This was the only way to educate myself in all the arts and crafts. There are so many areas in this project which are beneficial to various funding agencies. So, it has becomes a never ending symbiotic relationship between me and others.

You have also said, “As Brahma of the Pushkar is the father of the artisan, so is Phalke of Trimbak given the title of father of Indian cinema-my two obsessions.” – how important is this inquiry into the figure of a father for you?

There is a deeply ingrained image in my mind of the story of Brahma and his five heads, which is a generative image and excites my imagination. The story goes like this:

One day, Brahma, the father, the creator, was sitting by himself and he created a little girl from himself. The girl stood facing her father, the Brahma. She was happy in the beginning but suddenly got terrified, seeing the lust in her father’s eyes. So she moved to the side. Brahma did not turn his head, he just sprung another head on the side to look at her. She again turned and in this way, the four heads sprung from Brahma’s neck keeping a track of her terrestrially in all four directions. So she flew to escape his gaze. A fifth head sprung to scan her in the sky. An adolescent Shivgana(aspect of Shiva)- Batuk Bhairava- not understanding the basis of the play of nature between the creator and the creation, in rage, cut off the fifth head of Brahma. The head stuck to his hand and with that pain, he aged and turned into an old man himself. Something similar with Phalke that I want to arrive at…

You have talked in the past about cinema’s historical preference of the temporal montage over the spatial one – the latter being the one which facilitates an arrangement of shots that depict actions taking place not one after the other; but simultaneously, only in different spaces – do you think the cross-cutting techniques employed by Jean Pierre Melville, Edward Yang or Fred Zinnemann; or the narrative schema employed by Quentin Tarantino or Jean-Luc Godard were attempts at the presentation of simultaneously occurring events in different places?

There cannot be simultaneity because the audience will watch the cross cut events in a linear way, in time. The spatial montage can function in cinema like the way it does in Mughal miniatures, many actions, of different volumes, in the same space.

Expressionist cinema does this, often, where multiple images are aesthetically unfolding from the same horizon- different from the clumsier split screen.

Who were your formative influences while growing up? Which were your favourite films?

Andy Warhol, Bhupen Khakar. A lot of friends. Navjeet Singh, Rahul Dasgupta, Arun Khanna, Manohar Shyam Joshi. Roman Polanski. Ozu. Bunuel. Alan Resnais. My favorite films include- Tokyo Story, Life Upside Down, Days of Matthew, Intimate Lighting, Nazarin, and My American Uncle.

You have talked about the emergence of the new Indian cinema in the 70s being a result of realistically set literature that was the precedent of that cinema. How important do you think is the role of literature in shaping the aesthetic of cinema?

The text based cinema will have a different aesthetics and would depend on the source. Like My American Uncle is based on an essay by a biologist, or the Iranian films- Wind will Carry us or The Taste of Cherries is based on Camus’ essay from the Myth of Sisyphus. Or say, taking a text from a short story, novel or epic will lead to different kinds of cinema. If you like at Ray’s films, Bibhuti Bhushan takes him somewhere else and Rabindranath Tagore takes him somewhere else. During 70’s when Mrinal and Ray were sourcing their films from the same kind of a text, say, Samresh Basu, Shankar, Sameer Ganguly, their films look alike, you cannot differentiate between Interview and Pratidwandi. At the same time, there is a different kind of cinema that does not depend on the literary text. And uses the liberties that cinematic imagination provides with, constructed shot after shot. You can see that kind of films in early Roman Polanski.

Where do you see the position of the truly independent and experimental filmmaker in the nation today?

Digital film making is the way.

Finally, do you believe the attainment of pure cinema is a dream possible today, or do you, like Peter Greenaway and Godard, believe that that possibility has long been exhausted; and that cinema can no longer rid itself of the influence of text? Can an image, thus, finally detach itself from a word?

If you take cinema as an activity, and an empathetic tool towards the consciousness around, I think it is possible

(Published In Indian Auteur: Jan 2010, issue no-8)